Embrace the Struggle

by Darius J. Jackson Sr.

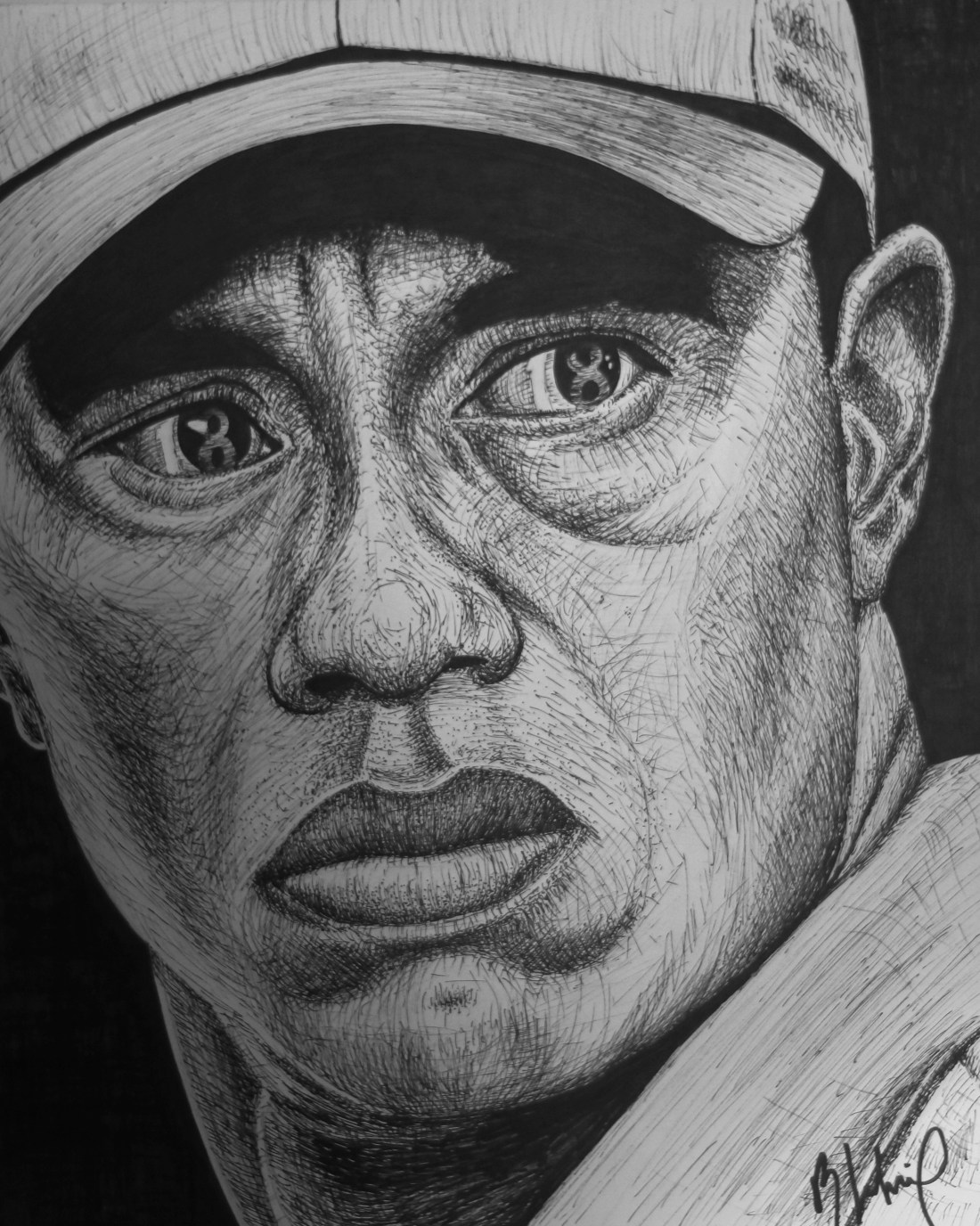

Muhammad Ali

by Jacob Miller

The Bull

by Austin Biggerstaff

The Trees’ Calling

by Claudia Lamp

Walking

by Florence Schloneger

White Guy

by Jacob Miller

Embrace the Struggle

by Darius J. Jackson Sr.

Muhammad Ali

by Jacob Miller

The Bull

by Austin Biggerstaff

The Trees’ Calling

by Claudia Lamp

Walking

by Florence Schloneger

White Guy

by Jacob Miller

Joseph Harrington: On Listening, Blue Clover, and Rest Stop Inspiration

Interview by Sutton Welsh

Audio:

On April 17, 2015, professor and poet Joseph Harrington visited Bethel College. Harrington is the author of 2011 Things Come On {an amneoir}. In his poems, Harrington combines the events of The Watergate scandal and his mother’s battle with cancer. His book explores the literary category of documentary poetry, which Harrington has spent a great deal of time researching. He also has studied experimental non-fiction, cultural studies, and political philosophy. In 2011, Harrington was a Pushcart Prize nominee, and for the years 2013-2016 he received the Conger-Gabel Teaching Professorship. He is currently a professor of English at The University of Kansas in Lawrence. Harrington spent his day at Bethel by talking about careers in the creative arts at a brown-bag lunch, helping students edit their poetry, and visiting Dr. Siobhan Scarry’s literature class Studies in Poetry: Archivists and Agitators. Although his schedule was hectic, Harrington sat down at Mojo’s for a cup of coffee and an interview with YAWP! editorial staff writer Sutton Welsh.

Sutton Welsh: Who are you reading currently?

Joseph Harrington: Well, a wide variety of things. For my graduate workshop, I just read Aria de Capo by Edna St. Vincent Millay, which is a play in verse … which I’ve never read it before. I’ve known about it for a long time, but I’ve never read it. I’m reading a book called The Do-Over by Kathleen Ossip, which I was privileged to read in manuscript before it was out. We exchanged manuscripts. A book called Many Small Fires, which is another book of poetry by a woman named Charlotte Pence. It’s her first book. I’m reading an anthology that just came out called Essaying the Essay. It’s edited by David Lazar, who edits Hotel Amerika magazine. It’s essays about the essay. Weirdly enough, I’m reading it cover to cover, which I don’t usually do with anthologies, but it’s really interesting. I’m getting kind of seduced by the essay as a form. I just read House of Deer by Sasha Steensen, who teaches at Colorado State. It’s about her growing up on the Mississippi — on a back-to-the-land, kind of commune-type place. I recommend all of those. They’re all worth looking at, for sure.

SW: If you were starting out as a poet, what would you suggest reading to spark the imagination?

JH: A lot of different poets, because what’s going to spark one person’s imagination won’t for another — poets and also all kinds of stuff. Marianne Moore subscribed to hundreds of publications, many of which were scientific publications. You’ll see a lot of American scientists’ quotes show up in her poems, out of context. She subscribed to The Journal of American Orthopedics — all kinds of stuff. You can draw inspiration both in terms of material and in terms of putting words together from anywhere. But it’s important to read a wide variety of poets to see what’s being done now, by other people your age, or at least other people who are alive now. We teach English courses as literary history. You take the Romantics, then you take a Whitman and Dickinson course, or you’re studying Yeats. These poets in their time were very ground-breaking. But that was then. Things have changed. You need to get a sense of what’s being written now. One thing I recommend if you want to publish is to browse journals. A lot of journals are online these days, and they’re really easy to browse because of that. The website “New Pages” has a pretty comprehensive listing of literary journals, with links to the web pages, all different styles. Just to write, write what’s happening to you, whatever you’re interested in.

SW: Do you have any creative strategies to help with writer’s block?

JH: It can often help to have a procedure, however arbitrary or random. Whenever I give my class a writing experiment to try, I always do it myself, because I often end up writing something unusual. For instance, our common book next year is A Farewell to Arms by Hemingway. So last week, I copied a bunch of pages, circled paragraphs, gave one to everybody, a different paragraph. Then I said, circle every fifth word, and now, list all the words down the side of the sheet of paper. Everyone had to use two columns. I said, “Now the game is to make a poem out of just those words and use all those words.” Right away, you don’t have to worry about what’s the right word, you’re using these words. I think it takes some of the pressure off, because the way we think about poetry typically is that the muse is going to inspire you, or that you have something inside of you that needs to come out, needs expression. But it doesn’t always work that way, and it certainly doesn’t always work that way by itself. I think having something from the outside to draw you forth to write things that you would not write otherwise. Whether it’s writer’s block or writing at a different vocabulary, games like that can be very helpful. Or even finding a text that has been written and erasing parts of it, so that you create a new text. There’s a book by Ronald Johnson. He grew up in Ashland. It’s called Radi Os. It’s an erasure of the first book of Paradise Lost. He keeps the words and the phrases in the same place where they were in the original, but he tells a completely different story than the original. A much more humanistic — kind of rude — but you still hear some of Milton in there, too. Stuff like that where there’s something on the outside to be a catalyst. That would be my main piece of advice. Also, to read. If you’re reading, or you’re at a reading, it’s more likely that the part of your brain that does poetry is going to be activated.

SW: When you write, do you do it on your laptop? Or, do you prefer notebooks?

JH: It depends on what I’m writing. I do different ways under different circumstances. These exercises in class I do by hand, because I usually don’t bring my laptop. Typically the stuff I write, I write on computer, because I fiddle with them. It’s easy to change the line breaks or the number of lines in a stanza — actually see how it will look on the page. I’m very visual and I’m very into layout, and I like to see how it’s going to appear on the page. For that reason I like using a computer. Also, for some of my work I incorporate graphics and pictures. That’s easier to do on a computer, although there’s no reason you can’t do something in longhand, with a picture on it and scan it. But that’s what I do. That’s just my taste. Or if I’m on a trip, and I don’t want to take my laptop, if I have something to write, I’ll write it down. I keep a little book. I keep a notebook at all times, because in recent years I find that I don’t really like to sit down and just write. We talked about writer’s block, and here’s another strategy: I listen. I listen to what I hear people saying, what I hear on the TV. I notice a bit of computer lingo or computer code, or something that just pops in my head that I find interesting. And I’ll write it down. Or I see something. It won’t all it end up in poems, like this won’t probably end it up a poem, but I stopped at the Emporia rest stop on 335. There was this moth carcass so I wrote, “moth, spotty. shifted in wind, showed natural tan underneath.” It was this dead-looking thing, and it turned over and it was this bright, vivid tan color. Stuff like that happens all the time in your day and you never know when it’s going to happen. Or when you’re driving … that’s the worst. So it’s useful to have this, or to know how to use a recording device really well. Then what happens is I put these in what I call “Word Collection,” that’s the name of the file. Sometimes I will go through and say which ones go with which. And I’ll put them all on a page and arrange them in various ways, maybe toss some out or add something to it. That’s how I’ll compose them all. That’s one way to go about it. I was walking across the soccer field to the bus stop the other day, and I looked down, and there’s this line of blue clover. Of course, it was where they chalked the field. It’s totally surreal if you take it out of that context and explanation. It’s something that I saw in everyday life — green clover next to blue clover. There’s something about that. I don’t know what I’m going to do with that, but I wrote it down.

SW: If you weren’t a professor or writing poetry, what would be your dream occupation?

JH: Oh, Lord. My dream occupation? Well, the first thing that comes to mind is majority leader in the U.S. Senate. [Laughs.] I come from a very political family. During grad school I did political organizing. It’s kind of a sideline, or alternate/default Plan B kind of profession. And I also read Robert Caro’s biography of Lyndon B. Johnson. The title of that volume is… Master of the Senate. He was so good at getting things done with a group of people, which I’m not. Basically, I would never have that job. I would hate it if I had it. But, boy, I would like to have the skills that would enable me to do it, I guess that’s what I’m saying.

Snowy Mountains. Oil Painting. Bethany Hamill

Ice Lion. Oil Painting. Bethany Hamill.

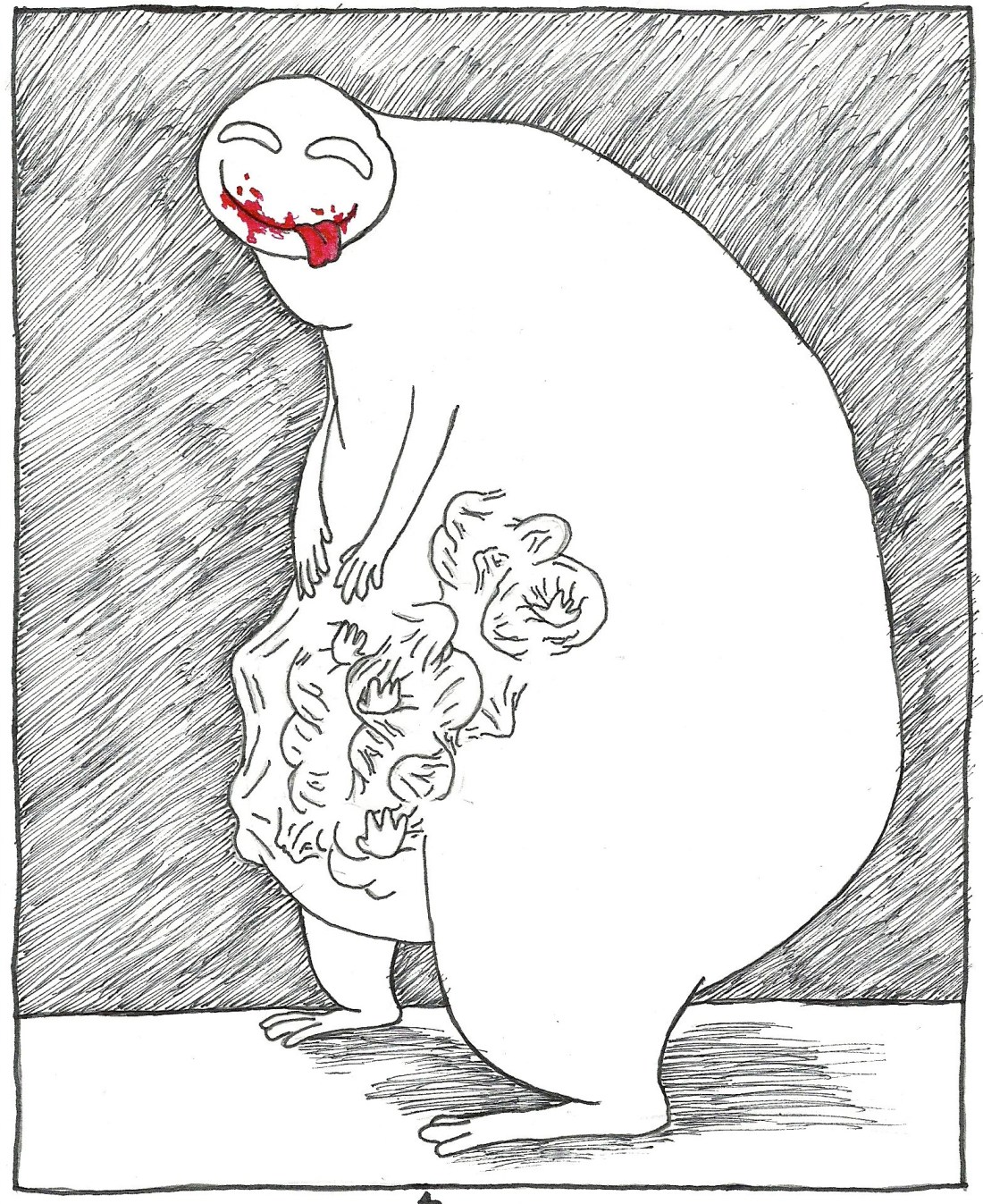

Cool Story Bro. Pen Drawing. Jessie Pohl.

Tiger. Pen Drawing. Brian Krehbiel.

Art by Brittny Czarnowsky

Art by Zane McHugh

Art by Brittny Czarnowsky

We Mountains

by Abigail Bechtel

Love like wasps

flow like ice

key to a loch

that unlocks nothing

remain like dandelions

sink like helium

my butter half,

melting in the sun

fly like penguins

weep like crocodiles

and leave

like

mountains.

Cloud Meetings: Utah, Mine 4730

by Katie Schmidt

Every afternoon the clouds consort, meeting over lake Powell, conspiring to rage, billowing into wicked silk pillars—they slide over land and launch shadows onto baked valleys. A moment of shade brings creeping skinks out from under the sage. The jackrabbit flicks his black tipped ears. The clouds travel, as planned, in a savage pack, hunting the desert for buttes to drench and erode, for beetles that can be floated out of their holes. Sunbaked chainlink burns lattice work onto the backs of migrants on the clock. They lean on it, eating lunch and dust. Eat fast—back into the mine before the rain. Already a gauzy curtain on the nearest ridge; it washes and creates washes, wetting even the gophers in their dry packed solitude. Newborn streams run with urgency and mineral red, rushing off with tiny fossils, arrowheads, bones, plywood and metal fittings, uranium ore—soon-to-be relics of ancient people who worshipped a God called Industry.

Saturday Morning in Which I Belong

by Elizabeth Schrag

We went for a run

Feet pounding

Breath coming hard

Legs aching and cramping

Chests tightening with effort

You asked me to tea

Scones

Perfect triangles

Filled with fruit and nuts

A sprinkling of sugar.

The all-familiar comfort of

A mug, resting delicately

In my hands.

NPR

I never liked it before.

But I laughed along with you

My inner liberal

Beginning to find her voice.

I can see a line of Saturdays

Stretched out before me

Taking me back

To where I belong

My mother

Baking in the kitchen

Batting me with a dishtowel

A line of sorrow in her brow

Not because of the life she chose

The reason I always

Attributed it to.

But rather because

This life is passing her by.

I would rather spend my days

In a warm kitchen

Filled with humor

Laughter

Family

Than in a haze,

Hungover, a half

-empty bottle

Of Burnett’s

Bitter as

Shame

Self-hatred

And denial

That a wasted life

is the only life

I am worth living.

Maybe I don’t

Have to run away anymore.

Maybe

I can just run.

Giants

By Will Shoup

The Queens Giant is a poplar.

450-500 years old and still kicking,

however trapped it may be;

the fence around it is ten feet tall

and barbed at the top.

It keeps good company

among tall men. Imagine them visiting

old Queens Giant, one by one:

first, Robert Wadlow, with his awkward

gait and child’s smile. He laughs a lot.

He laughs like a steam shovel cough.

He fixes his glasses over and over.

The lenses are very thick

and as big around as your fists,

and they droop off his ears

and down his sepia nose

toward the ground.

Next, Felipe Birriel, who lived to 77.

He runs his palm along the trunk;

he feels the diamond lenticels;

he dreams of Mona Lisas.

He can smell the coffee bean rain

and the sugar cane ocean spray,

and he leaves a few grey hairs

in the cracks in the bark.

Then Manute Bol,

a full four inches shorter.

7 feet and 7 inches.

He lies down in the roots

and stares straight up the trunk.

Old Queens Giant creaks good-humoredly.

Bol leaves and goes back

to his second wife, his ten

kids. He’ll never block

a shot again, and the ache

of the old tree’s bucatini limbs

pounds between his ribs.

Finally, Bao Xishun visits.

He flies into JFK and is searched

for herdsman contraband by TSA

officers. He comes up clean.

He doesn’t get too close to the tree.

He tries to remember the others,

for their sake, not his,

but he doesn’t remember them well,

only that they were all very tall.

Here, they must finally have felt short.

Bao Xishun’s diet consists mostly of vegetables.

He once pulled shards of plastic

from the stomachs of two dolphins.

He was the only man in China

with long enough arms to reach

in there and get it all out. Before

the operation, the dolphins had been depressed,

but we never heard how they coped

with the loss of the plastic shards.

It’s summer here and in Mongolia.

The leaves on the poplar

have one glossy side

and one matte side

and a sideways stem

that flutters in the wind.

Bao Xishun watches the leaves

show off for him. He claps politely.

He often longs for the grasslands,

but at least this is the last stop

before he gets to go home

to his wife and their daughter.

The little girl is just a sapling:

five years old. One day,

she may be very tall

or maybe not tall at all.

He pats the old trunk

and smiles and moves on.

In-Between Prayer

By Will Shoup

Doce to dos y media, this día—

Dios! Sprinkle, immerse, learn,

know, memorize—molten tartread

stripes Main like glue. My bike’s tires

make tracks in the tracks, and I pray.

Barn swallows fork over the street

between their muddy nests. Two families’

homes: their home. Above a prairie porchswing.

Below a balcón in Argentina. And all the sea

between. Lord. Fuck. Flight. Tight,

milk-churn slosh of pedals

against my feet, and the sparrow

squeal of the left pedal with every thrust.

It needs oil. There’s no way there’s

time for all of this. Write this poem,

read Wordsworth, class, b-ball, dinner, recursive—

loop!—the Spanish test, tomorrow.

I pedal harder. My breath tattoos a rosary

against my chest and I pedal and pray

for the God of time to send me

a temporal anomaly.

A Will-sized warp bubble:

the time to get the book. The cheat grass—

Drooping Brome—spits seeds

into my ankles’ skin, and I stand

on the pedals and cut

across the railroad backbone that separates

North Newton from Newton, proper.

There’s little left:

tyrant wind and blue and

the old brown custom detailer filled

with automotive decay and fuck and

Lord the space across the river

on the bridge and ragweed and soldier-

tall hemp and the blue of the river under

and froth and bubbling brown

and riverfoam and that space

contracting: this Greyhound-weathered

backpack; this unfull Nalgene; this skin;

these knuckled white fists

on tape and metal ramhorns.

I gasp and cross the second riverbridge.

West, the dust from corn and grazing

combines thickens the horizon air,

and below, debajo de, beneath my feet,

my red wheels punch the asphalt

face of the Earth.

I will never be on time.

I am all the space in the world.

Pique-Nique, 1946

By Katie Schmidt

He chose a place among the brome grass,

shaded and still, to spread the cloth and unpack.

Tall and drooping, pulled into mournful bends by the weight of their seeds,

the feathered florescences leaned over the edges of the blanket

to hear the couple’s conversation.

The seed heads

hung pendulous and limp,

ashamed to be eavesdropping. They kept their heads down.

They kept quiet.

She opened jam jars. He compared her to the sunshine.

They exchanged comments about the uncommon dryness of the season.

They took turns remarking on the beauty of such

an undisturbed place.

From its perch in the sagging metallic remains of a windmill

a kingbird scanned the plain in all directions, looking entitled to the land.

With his yellow belly and proud posture

she thought it resembled a soldier surveying the aftermath of battle.

He asked about the French she learned there. He asked if she would ever

consider working here as a nurse.

She thought the sun’s gentle heat on the back of her neck

felt like warm blood rolling on her skin.

Instead she answered,

Mon dieu. That was the only French she remembered.

It rang out, then – clear and sharp, from the center of all things.

from the grass and the sun and

the kingbird too.

That foreign moan echoed in her hollow body, tightened her face.

Ashamed and frightened, the little yellow soldier darted away into a hedgerow.

He asked if she enjoyed bird watching.

The brome grass sagged further, a breeze helping their heads to shake.

The wind swept the place clean as it passed; all noise rolled away to die in the fields.

She murmured something about the dryness of the season.

So soon, she thought.

The seed heads had all withered,

tawny and fragile

so soon.